BRATTLEBORO, Vermont – Sixteen years after the first PGA Championship in 1916 the powers-that-were must have had their first inkling that match play could make for a really long day. Two of the 1932 matches made it to the rare 40 and Over Club—matches that not only made it to the scheduled 36th hole, but then beyond for the footsore combatants. Talk about your barking dogs!

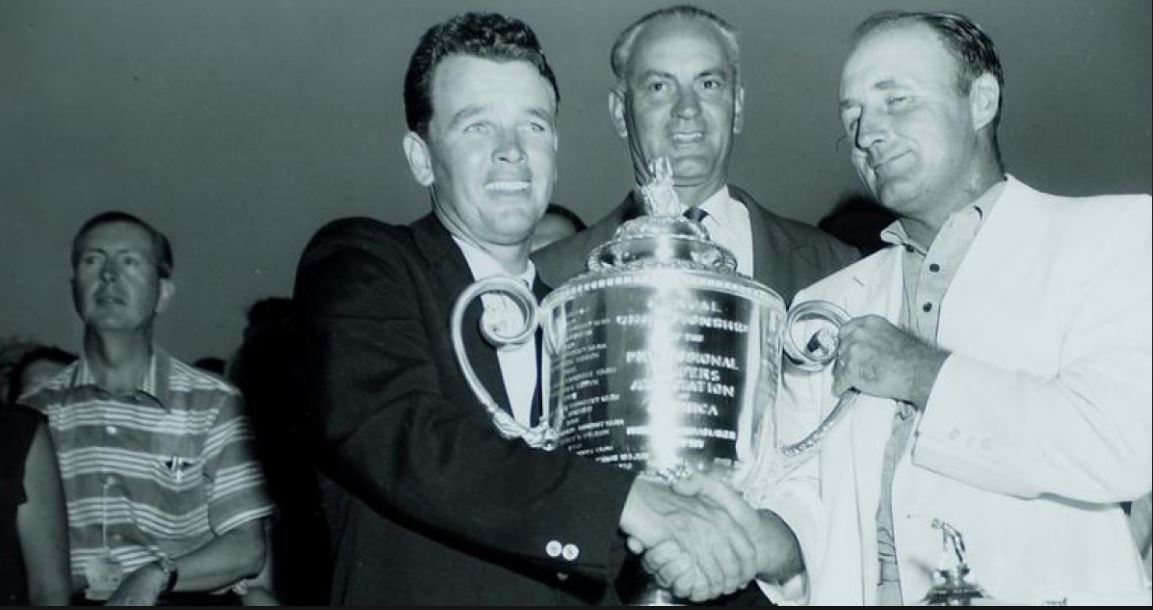

There were only five such prodigious hikes in the Championship history, and there the matter rests, since match play ended after the 1957 tilt. (Take these trivia bets with you to the bar—last player to win a match play PGA Championship? Lionel Hebert over Dow Finsterwald, 3 and 1. First to win in stroke play at the 1958 Championship? Dow Finsterwald.

The first such long march came in a first-round match in 1921 at the Inwood Country Club in New York. Even former PGA historian Bob Denney admits the details about that 40-hole match and its winner, Charles Mathersele, are obscured by the shroud of time. Of his opponent, Johnny Farrell, much is known, as he went on to win the 1928 U.S. Open.

All that is really clear about Charles Mathersele is that he must have been exhausted, as he lost in the second round to Cyril Walker, 4 and 2, and promptly exited the record books for all time.

It was eleven years before the Club opened its doors again, but then it installed four new members, including the great Walter Hagen, a record five-time winner of the Wanamaker Trophy. And with Johnny Golden in 1932 the Haig also set the all-time record for the longest match in PGA Championship history, at the Keller Golf Club in St. Paul, Minnesota.

The ending was not what the champ was looking for, however. When Golden poured in a 10-footer for birdie on the 43rd hole, Hagen made his early exit to look for the Epsom salts. Golden, who would ultimately win nine times on the PGA Tour, pooped out in the second round, losing to Al Collins.

Amazingly, elsewhere on the same course on the same day, Bobby Cruickshank and Al Watrous were staggering through a 41-hole match. This one was more extraordinary in the sense that Cruickshank looked to be so dead and buried at the 22nd hole (nine down) that Watrous took pity and conceded a downhill six-footer his opponent needed for a half.

Cruickshank then promptly rose from the grave and won nine of the next 11 holes and by the end it was all square. The pair then traded punch for punch over four more holes. But on the 41st Watrous flinched, missing a three-footer, and headed home.

If match play in a major seems a quaint notion these days, how about the stymie rule? It was still in effect in 1948 and effectively ended Sam Snead’s chance to advance out of the quarter-final bracket. The Slammer was battling Claude Harmon over the grounds of the Norwood Country Club in St. Louis, and Harmon had him over the ropes after the morning round, 5-up off a 64.

But Snead turned in a mirror image 64 in the afternoon, drained a five-footer at the last to square the match, and looked to be in command on the first extra hole when he put his ball fewer than seven feet from the cup. But Harmon knocked his ball inside Snead’s and had the perfect stymie. Snead was forced to putt around the ball, settle for par, and proceed with the match.

Five holes later it was still proceeding, and both players left their second shots an almost identical 20 feet away on the 42nd hole. They had to bring out the tape to decide who was away. Harmon had first crack, and he rammed it right into the hole. Snead couldn’t answer, and that was that. The next day poor Harmon had to go an extra hole again in the semi-finals, but this time came up empty-handed.

“Match play is an up and down thing. It was like you were up on the edge of a cliff, constantly dodging guys who were trying to push you off,” said Jack Burke, Jr. from his office at the Champions Club in Texas.

He should know. Burke won the title in the 1956 Championship not long after copping the 1956 Masters as well. He was well-prepared, a battle-scarred veteran from the year before when he and Cary Middlecoff took a long march around the Meadowbrook Country Club near Detroit in the 1955 Championship. Burke remembers it well, and why it took 40 holes and nine hours:

“We came to the last green and I was 1-up. Middlecoff had about a 25-foot putt, when he sat on his bag and lit a cigarette. The club pro, Chick Harbert, said to me, ‘Why don’t you call him for slow play?’ I said, ‘Why don’t we let him see if he can make it.’

“I’ll be damned if he didn’t make that putt. That put us even and then we went out and played some more. By that time the evening sun was bearing in on us and shining in my eyes. I hit one fat into a greenside bunker and couldn’t get it up and down. He made a par and so that was it, he beat me there.”

But Jack Burke, Jr. has really gone the distance. Of all the players who took part in these epic matches, he’s the sole survivor having turned 98 in January. And he still practices a couple of days a week, if admitting, “Just so I can talk to you about it.”

https://www.pgachampionship.com/

Leave a Reply